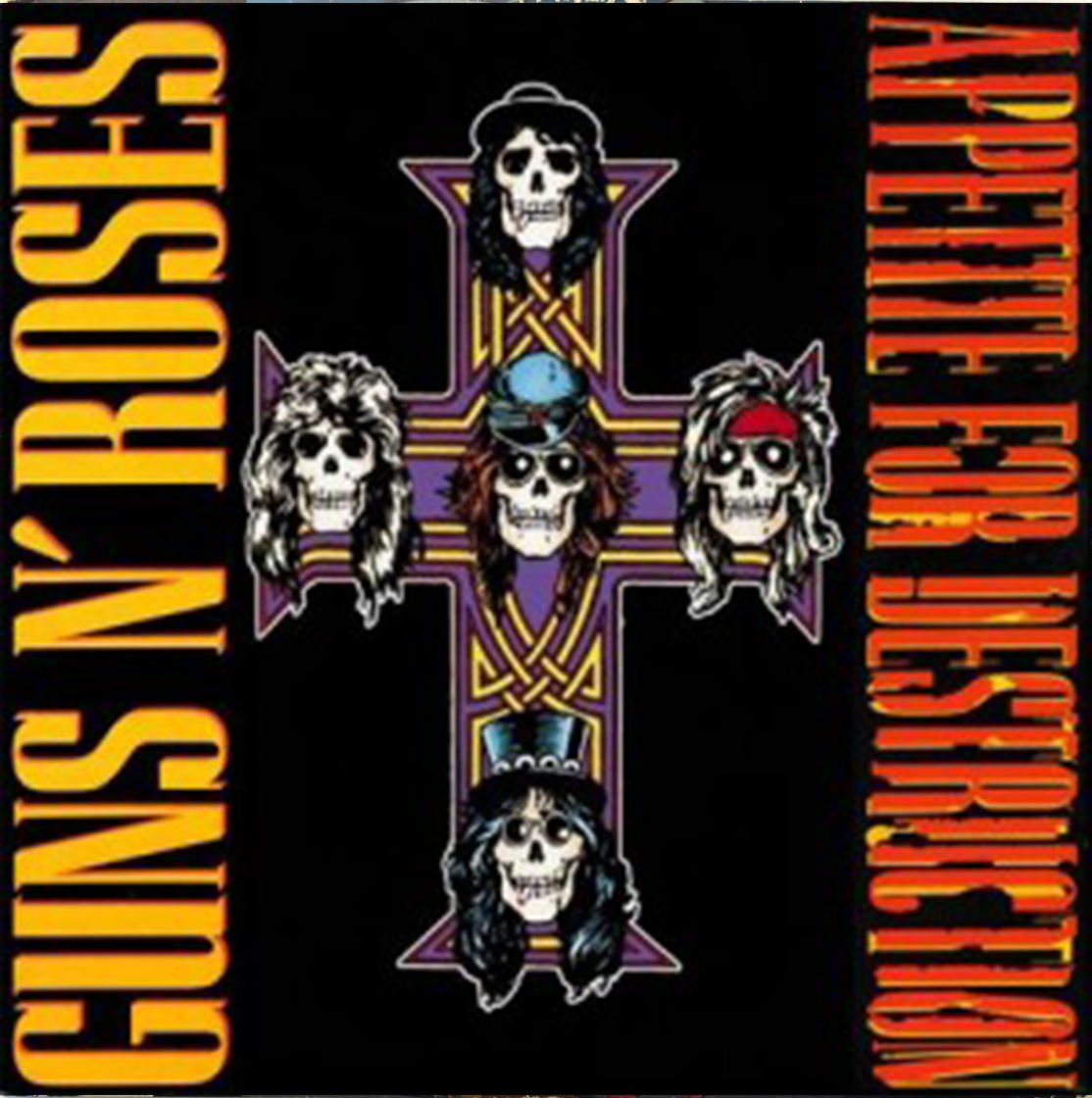

Guns N’ Roses’ debut album Appetite for Destruction (1987) marked the resurgence of classic hard rock after years of New Wave pop. The album was welcomed by fans who longed for authentic in-your-face rawness, as a number of tracks represent “destructive” lifestyles and activities such as heroin addiction (“Mr. Brownstone”) and sadist culture (“Welcome to the Jungle”). The songs were vehicles for listeners to feel a part of a counter culture that had been seemingly anesthetized by the Reagan years. But there was more than just the music that helped GNR stir controversy and increase record sales.

After producers said it would be distasteful to use the exploding spaceship Challenger as cover art, Axl Rose turned to Robert Williams’ painting Appetite for Destruction (1978). (What the album was titled before this is a mystery). Williams’ painting depicts a robot, often said to be dressed as Robert Crumb, founder of Zap Comix, the 1960s underground comic series that critiqued mainstream culture. In William’s painting, the robot has a bear trap head and towers over the woman he presumably raped.1 In the background, a strange creature - perhaps a Rat Fink-like Hell’s Angel with metal blades for teeth - floats towards the robot. While some critics have reported this character is poised to avenge the woman, the creature’s purpose is unclear. Knowing the graphic image would stir controversy, Williams recommended that GNR choose a different image, but the band decided to use Appetite for Destruction, arguing the work was “a symbolic social statement, with the robot representing the industrial system that’s raping and polluting our environment.”2 (Because GNR was fully committed to environmental activism, right?). Disagreeing with GNR’s interpretation, many stores refused to stock the album, leading GNR producers to create a second album cover that was less controversial. However, the original cover was placed inside the album, and feminist groups continued protesting, claiming the band was glorifying rape by using Williams’ image.

Williams, known for pop surrealism, “lowbrow art,” and his affiliation with Southern California car culture (the so-called Kustom Kulture and Rat Fink aesthetic of the 50s and 60s), claimed his paintings were “intended to have no more meaning than a picture on a cocktail napkin, and if they appear to some people to be more than tightly rendered cartoons, well, those people are right.”3 So what is the “more” to William’s Appetite for Destruction? To reveal Robert Crumb was a sex machine? Is the supposed avenger Williams, who reveals Crumb has an appetite for rape?

Williams has also been criticized for objectifying women, painting naked women atop or inside hot dogs, sandwiches, and tacos. When explaining why, he said because he loves a woman’s ass.4 While it is perhaps easy to understand the conflation of sex and food - important human drives - couldn’t it be argued Williams’ Appetite for Destruction and these other paintings illustrate women as objects of consumption? And isn’t it more believable this is what GNR had an appitite for all along?

1 As shown in the 1987 documentary The Confessions of Robert Crumb, Crumb explains his life may look quaint on the outside but “underneath it is a steaming caldron of sexual perversion, drugs, and neurosis.”

2 Goldstein, Patrick. 1987. “Geffen’s Guns N’ Roses Fires a Volley at Pmrc.” The Los Angeles Times. Aug. 16. Accessed Oct. 27, 2017. http://articles.latimes.com/1987-08-16/entertainment/ca-1533_1_artwork .

3 Deriso, Nick. 2017. The History of Guns N’ Roses Controversy-Courting 'Appetite for Destruction' Cover. July 27. Accessed Oct. 27, 2017. http://ultimateclassicrock.com/guns-n-roses-appetite-for-destruction-cover-controversy/.

4 Acid Head: The Conceptual Realism of Robert Williams. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHUMbgZhc0s